DEVOTIONAL LANDSCAPES

Our recollections of places are experiential. Novels, studies and analyses have been dedicated to some, while others have been surreptitiously internalized. A point on a map, an architecture fated to either endure or inexorably fall, but beneath stones and concrete, beyond immensities and fissures, what remains of them? What casts them into our memory?

In the case of Zawiyas, beyond their geographical and architectural pervasiveness, they refuse to be dispelled from the margins; they persist as a place-memory. Zawiyas, common centres or shrines of holiness in the Maghreb, are sanctuaries of spiritual and mystical explorations of Sufism in an Islamic context and affiliation; “the zawiya remains a central place where the triadic relation of practice (zikr), people (Sufi adherents guided by a shaykh) and place form an interactive sacralised space as performative force”.[1] The term “Zawiya” takes root in the verb “Inzawa” which means in Arabic “to withdraw, to isolate oneself or to be apart”. It refers to a conceptual and physical space—typically a corner, cell, or oratory—where individuals come together in search of solace and serenity, often through the veneration of a patron saint. Functioning as religious institutions, they typically encompass a mosque, spaces designated for meditation and scholarly pursuits, as well as lodging facilities for pilgrims and disciples.[2]

These sacralised spaces are embedded in the urban structure of the landscape and are ubiquitous throughout the North African landscape. Both physical and metaphysical, these shrines are scattered throughout the cityscape. They often function simultaneously as a tomb that typically bears the name of their eponymous local saint or founder; and they are at once sites for memorial reverence and worships rituals. A great deal of importance is also lent to the musical trajectories and trance that are associated with certain activities and practices, such as the Īsāwiyya performance. Catalina Swinburn’s exhibition Devotional Landscapes meditates on these sites as conduits of healing and devotion, born from her artistic fieldwork at various religious and archaeological sites across Tunisia. The exhibition is a contemplative response to her research, to her immersion into the practices and etiquettes of this specific spiritual heritage and patrimony. The fruit of her exploration serves as an invitation of reflection, where the physical merges with the transcendental through weaving and sonic textures. Swinburn’s new body of work straddles both archaeological and contemporary languages; it marks a visual recognition of a geography where architectural landmarks are intertwined in her work, interlocking her materials as if they were a mosaic, retracing connections in the Maghreb through Zawiyas. Situated across the main space and mezzanine, the exhibition presents sculptural weavings, a collaborative piece with Tunisian artist Mohamed Amine Hamouda, accompanied by a video documenting the process, and a sound piece that combines the movement of ritual music, the weaving of paper, and the interplay of sound and motion.

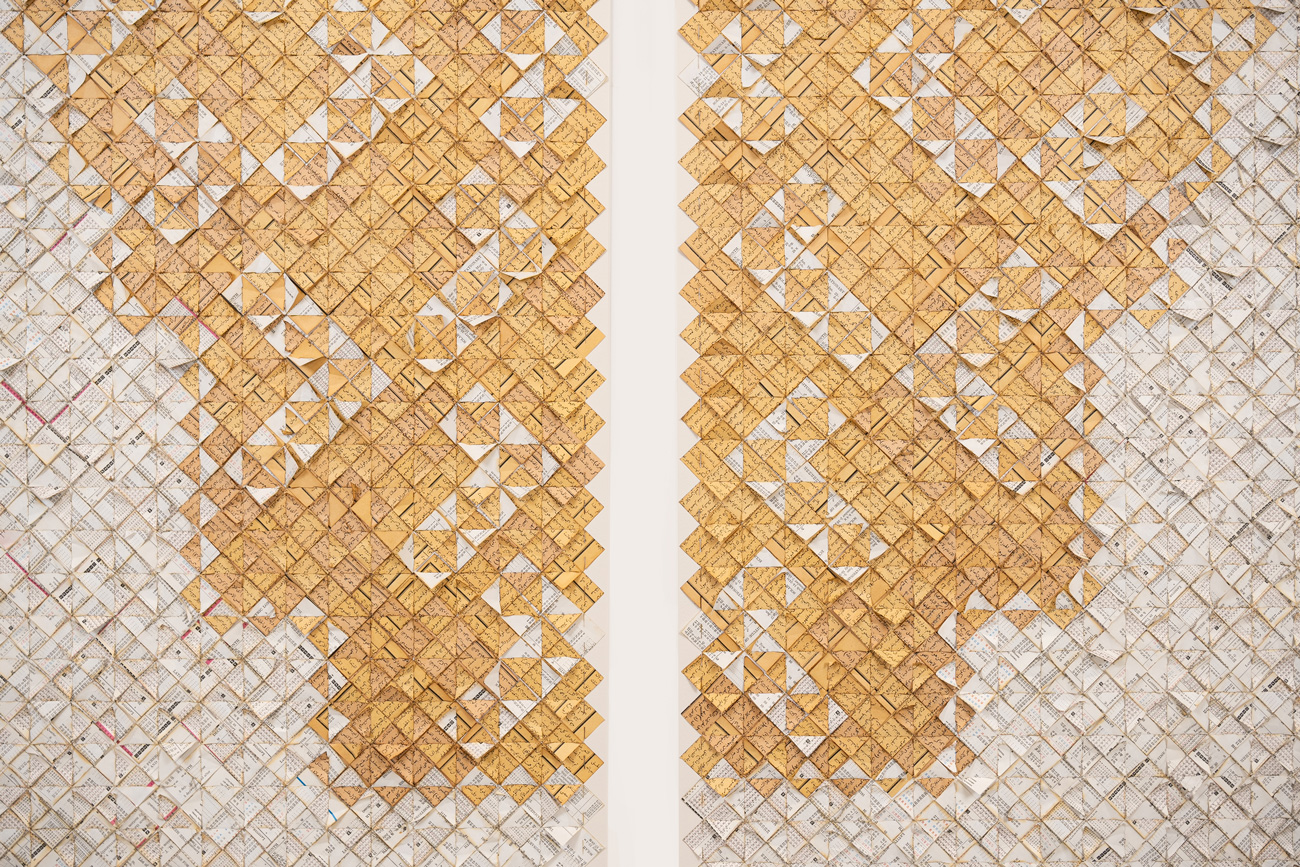

A constellation of works follows a tripartite structure, such as the Īsāwiyya Hadra’s ceremonial ritual. These sequences lend their titles and polyrhythms to Swinburn’s Hizb, Shishtrī and Hadra. Their arrangement does not compose a linearity but is rather a propagation of a landscape. Each piece of this series is the woven enactment of the tempo diagrams and rhythmic trajectories of each layer of the sections, both vocal and instrumental. The hizb asserts a Sufi legitimacy, the shishtrī highlights the role of the cultivation of Andalusī music, featuring Andalusī poetry and mālūf musical modes, melodies, and structures; and the Hadra reveals its command of trance states. Together, they form a cumulative, teleological experience in which successive strategies of intensification unfold, ultimately converging in the ritual climax. The Hadra, as both culmination and form, embodies both cultural consciousness and a musical process itself.[3] The intervallic, stepwise nature of their musicality is reproduced through Swinburn’s weavings; their progression rests on two inseparable cores: recitation and repetition. Repetition and cyclicity create the very conditions of the Hadra—sonic, temporal, and spiritual. Each recurrence is not mere sameness, but is in a constant relation to what came before and what is yet to come. These threefold recitations are coordinated illustratively in a simultaneous way to how Swinburn arranges her dismantled paper fragments—through a gesture that atomises and illuminates their final totality. Mjarred, a piece that takes its name from the middle sub-section of the Hadra section, involves a repertoire of songs in the Īsāwiyya’s iconic five-beat handclap patterns. It introduces a percussive layer to the a cappella opening. Structurally, it follows the sequence of mālūf nūba. Antiphonal call-and-response, first introduced in the Hizb, is summoned again with density alongside other components of Mjarred. It is positioned within broader ambient Sufi soundscape—one where individual and communal trances coexist. It is specifically the ending of this section that takes the whole ritual to a dramatic intensification of experience, where musical, spiritual, and corporeal thresholds—previously unattained—are concretized.

This fascination with sound greets us as we enter, veils our shadows, reverberates beneath our soles, roaming with us in the space via the sonic compositions recorded at the Zawiya of Sayyda Mannūbiyya, the weaving of paper in her studio, and the narrations of notes, quotes and discussions that Swinburn engaged in. Simultaneously, the artist culls inspiration from both the sonic and architectural, as Mjarred and To Seek Refuge—which towers on one side of the space—take the form of the negative space or rear construction of a Mihrab, the prayer niche found in both mosques and zawiyas. The numinous junction is extended in the large tapestry Illuminated Pages I which is informed by the manuscript of the Blue Quran housed in the Bardo Museum. Through it, the connection to the divine bypasses the urgency for verbal articulation or legibility. Swinburn imagines the tapestry as an open book, its pages reaching for the elusive light of enlightenment. Their dual flatness and convexity defy a fixed time and space; they lean under gravity, but never in obliqueness. They contain a release that never drifts in the cracks of paper. It is as if they create a porous opening, a portal on the backgrounds they are mounted upon, or bulging outward from. A yearning hovers over; lend yourself to its cadences and the echoes shall appear. It is in this lapse where we find ourselves, a space for solemn soliciting. They occupy an incommensurable temporal interstice— are they historical relics, excavated from an ancient time, relaying us to another undetermined time? Or are they garments of futurity, propagating intangible messages, or retroactive sculptures existing in the now and here?

The exhibition marks the encounter and intersection of two independent practices—Catalina Swinburn and Mohamed Amine Hamouda—where their materials and ends collaboratively overlap. As part of her research, Swinburn made several trips to Gabès, witnessing Hamouda’s decade-long construction of paper from vegetal scraps in his studio—a space where they jointly created the paper for their shared project. In the mezzanine space, Swinburn weaves together this paper, made from fibres directly from palm trees from the Oasis of Gabès, utilising palm leaves and natural pigments. This paper was later engraved with knitting and crochet cotton cloths made by local women artisans, as well as gold leaf, culminating in the piece, The Phoenix Rebirth. Using 180 sheets of paper that they constructed from scratch, the alphabetic unit—commonly present in Swinburn’s practice through the use of discarded books—is absent in this piece; on empty pages, the engravings carry undocumented stories of craftsmanship. Here, the Latin Texo (to weave, to plait) and its participle Textus (text and texture) play interchangeably. In the absence of one, the other is summoned; for voices are not required to fill the void, but rather silence—which exists in relation to sound and language—may exhaust the subtext of their gestures. The constant tension of tearing and repairing, the trace of a testimony, the rustles on a surface, are all cradled in innumerable, ceaseless knots.

The backdrop of this exhibition, that is its documentation, is rendered into handmade twists and filaments, serried in infinite plenitude. It is in this devotional space where the artist deliberately situates us, a presence that beckons us forth to pause and step away from the overwrought ties of being, and to approach both solitude and companion alike.

Racha Khemiri | Tunis. May 2025.

[1] Desplat, Patrick A., and Dorothea E. Schulz. Prayer in the City: The Making of Muslim Sacred Places and Urban Life, 2014, p. 27.

[2] Idir, Lydia, and Abdelouahab Bouchareb. “Architecture and the Sacred.” International Review for Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development, vol. 11, no. 4, Oct. 2023, p. 152.

[3] Jankowsky, Richard C. “Ritual Reflexivity: Musicality, Sufi Pedigrees, and the Masters of “Intoxication””. Ambient Sufism: Ritual Niches and the Social Work of Musical Form. The University of Chicago Press, 2021.