If we take as our starting point the words of Jean Clair in “The Paradox of the Curator”, we must agree that after the Second World War, in a world without gods, contemporary art museums have go on to replace the sacred space of the temple. Socially and symbolically, templarity has been replaced by museumism. It is in the museum that the public regains their relationship with the sacred. However, this is an institutional illusion that laicizes the wish for transcendence, placing on the market a space of imaginary repair.

This proves to be the substratum on which the work of Teresa Aninat and Catalina Swinburn (A&S) is built, prepared to operate on the unsteady boarder situated between cult and artistic practice, through the use of ritual (performance) and objectual arrangement.

Nevertheless, these dispositions are subject to the legality of the script and they settle like correlated actions being carefully regulated. This privilege of the arts – of the image of the script – initiates control of the image of power that will be one of the chief characteristics evident in the work of A&S, an aspect that will go on to consolidate the scene script guiding the ritual like the conducting thread of a representation of the fault, for the benefit of a disposition of incarnation.

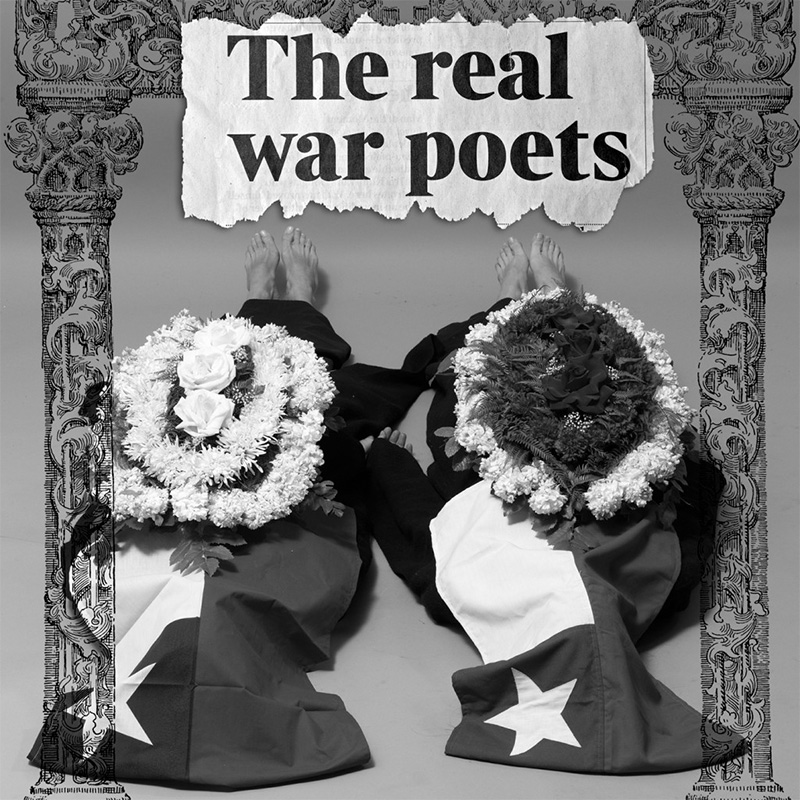

In the ritual, the actions of A&S shed the emblematic gestures of catholic intervention, emptying them of their theological determinations, but keeping their appearance as liturgical complexes that mime the historical repertory of sacred narratives, as if the whole history of painting, that is to say, a certain painting of the renaissance, was not more than an illustration of that said textuality, with its inventory of announcements, compassion, holy shrouds, Veronica cloths, etc. All these material references and gestures empty of their original charge can be translated to the critique of the art system.

The position assumed by A& in their performances is that of intercessors, whose role it is to secure a sort of mimetic tie with the most unfamiliar, in the heart of a monotheist universe that is aimed towards a faultless transcendence: the Creator and his creation. In this sense A&S reproduce the intensity of a true “conflict of the images”, like an erudite recourse in which the discourse that sustains their practice is elaborated without pause. All of their works are commanded by a mildly iconophobic principle. This is the reason that the performances are realized subtle and timid, retired from a space which requires from them a display of unlimited profuseness. This retirement highlights the discomfort of participating in a world – and in an art space – in which the notion of transcendence has been broken.

he relationship between the Creator and his creation has been broken. Therefore, in their works, the act of bowing down, in which they are put in the position of the believer, exposes their decision not to look indefinitely at the Icon; that is, the prototype of all icons. The believer only looks once at the model, hoping that it is directed towards that from which it came. As Guy Le Gaufey has shown in “Le Lasso Spéculaire” (Ecole Lacanienne de Psychanalyse, 1998), bowing down, “allows the given look to make its own way; to remount from the icon towards the prototype but above all, even further, from the prototype to the Creator.” This hypothesis assumes that the bow impedes the impossible clash of gazes that nevertheless attempt to be outlined. This figure of reference allows A&S to affirm by its absence the existence of a breakage or rather, the insistence of a failed transcendence, which sustains the conditions of reproduction of the art world. Although in a more decisive manner, above all it points towards the importance of nowadays submitting oneself to the base which configured, in the “Christian west”, the conflict of images (eighth century, Byzantium) and its effectiveness to reconstruct the imaginary Unit of the Word.

The previous means articulating a supplementary hypothesis intended to consider the usefulness of St Nicephorus’ Doctrine and the stage of Lacan’s mirror. For my benefit, Le Gaufey himself has sustained in the aforementioned book, that by defining the Christ-icon as a “mirror” it is necessary to think of it as a turned mirror, not reflexively directed toward the believer “but turned, via Incarnate Sons, towards the Father, toward He who since always and for always does not show himself.”

In one of their works – In God We Trust – initiated in the Museum of Contemporary Art (Santiago, Chile) in 2009, A&S reproduce the statement printed on American dollar bills since 1957. In that work they pieced together a burqa from one hundred dollar bills. The garment, which covers the head, nevertheless leaves the eyes uncovered. What is figurative in this work is the notion of the Holy Face, literalized with maximum rigor. It is necessary to mention some things on the matter: Constantine, on the eve of a battle ordered Christ’s monogram (the letters chi and rho) to be painted on the shields of his soldiers. Then, at the end of the fifth century, another Constantine ordered that all silver coins be engraved with Christ’s monogram, and adding a small cross above the Roman eagle. We are in the confluence of three significantly powerful axels: the power of the image, the power of the relic and the power of the Emperor. Christian iconography adopts with no difficulty imperial art; in the piece In God We Trust, A&S invert the terms of the polemic exhibiting how today’s imperial art effortlessly adopts Christian iconography.

The phrase “in God we trust” has reduced the role and the density of the icon as mediator on behalf of the Father, declaring the only visible paternity in the disposition of the imaginary planetary (of today): the dollar. Thus, the image of the dollar appears like a certificate that accredits the breakage of (all) transcendence. Why resolve to tackle the work of A&S from this perspective, not particularly common in the critique of art? Marcel Gauchet in “Le Dèsenchantement du Monde” sustains that whatever the force of religion, the essence of the transcendental as necessary to thought has been lost. It no longer plays a role that is principally explanatory, neither in contemporary knowledge nor in the politics of nations. However, the elaborate form of thought in that register are still operative, functioning in different metaphysical scenes, but responding to structural necessities in a symbolic space which would not know how to correspond solely to the religious sphere. In this debate, in fact, is the genesis of the relationship between the visible and the invisible, tied to a history of conciliar decisions which establish a solution of compromise in the relationship to the double nature of Christ.

The double nature discards all ideas of progressive “passage” from one to the other. The intercession of Christ does not “bridge” the two natures, but placing itself on the bank of the visible, it expresses the invisible. In this manner, in this text, the insistence placed on the bowing figure aims to direct attention to the role played in the genesis of A&S work, the prototype of the image (critical sign). In consequence, it recovers the infrastructural function of the Holy Face in the diagram of their works, taken as a whole. Hence the whole piece is a work about the statute of the image in the position of the collapse of the notion of transcendence, in contemporary art. But if it is an image, it refers to the image of the body as the only link for understanding the world. But most of all, to understand the world of art which comes about from the incessant effort of understanding, as is sustained by Luis Enrique Pérez Oramas, curator of the XXX Biennial of São Paulo, in the essay “Tangled Alphabets”, which talks about León Ferrari and Mira Schendel in relation to their exhibition in the National Museum Reina Sofia, Madrid, in 2010.

The point is that the reflection of an image, in A&S, is a way of elusively tackling the transformation of products of material consumption into products of spiritual consumption. For this reason I will finish this presentation by resorting to the quotation Pérez Oramas himself uses in the book of Louis Marin about the logic of Port Royal, in which he refers to the Eucharist as “the place where language, which speaks of the present, transforms and it transforms (…) but transforming itself in the subject of enunciation (…) being the problem, in every case, of recognizing how a body can be sign and true sign, and how on the other hand, a sign can be body and true body.”

Justo Pastor Mellado

Valparaíso, April 2012.