MEMORIES THAT REMAIN

Maisa Al Qassimi

The continuous change of territories and borders has always been a global concern. It produces an inside/outside situation within societies; it creates a new form of expression to ownership and belonging. These struggles have affected the upsurge in refugees and migrants crossing borders today. These are a some of the issues that are explored in Catalina Swinburn’s more recent series The Perfect Boundary a journey that started in 2015.

Swinburn’s practice investigates through a variety of media such as video, installation, sculptures and photography and the use of materials such as paper and marble. Many of Swinburn’s process starts with performance whether utilising her own body in the work or the act of performance it the artwork’s production. This embodiment and interconnection through time, place and space allowed the artist to express the human experience.

In this series, Swinburn combines the two performative forms by initially creating an object by the act of weaving. The materials used are archival sources from historic books such as atlases, archaeological and music. In The Perfect Boundary, 2016, Swinburn uses pages from an atlas from the 1970s, a documentation of a time where countries once existed and borders have changed. Theses archival pages are then woven into each that continuously modifies the shift of geographical lands. The interlaced sculpture here is worn by the artist in the performance and dragged across lands, creating its partition by recreating borders.

Where was that object in time and place before the performance? Has it taken the shape of my body? What memories will it have? What narratives will it tell and where will it go? These are a few questions Swinburn poses before, during and after each performance. She explains,

“The paper works have their own life. They become a sculpture, an abandoned body that has a history that traces the form. They gained a history and remind me of stitches of memory that remain. All the cultural catastrophes around the world where cultural sites have been displaced and others destroyed.”

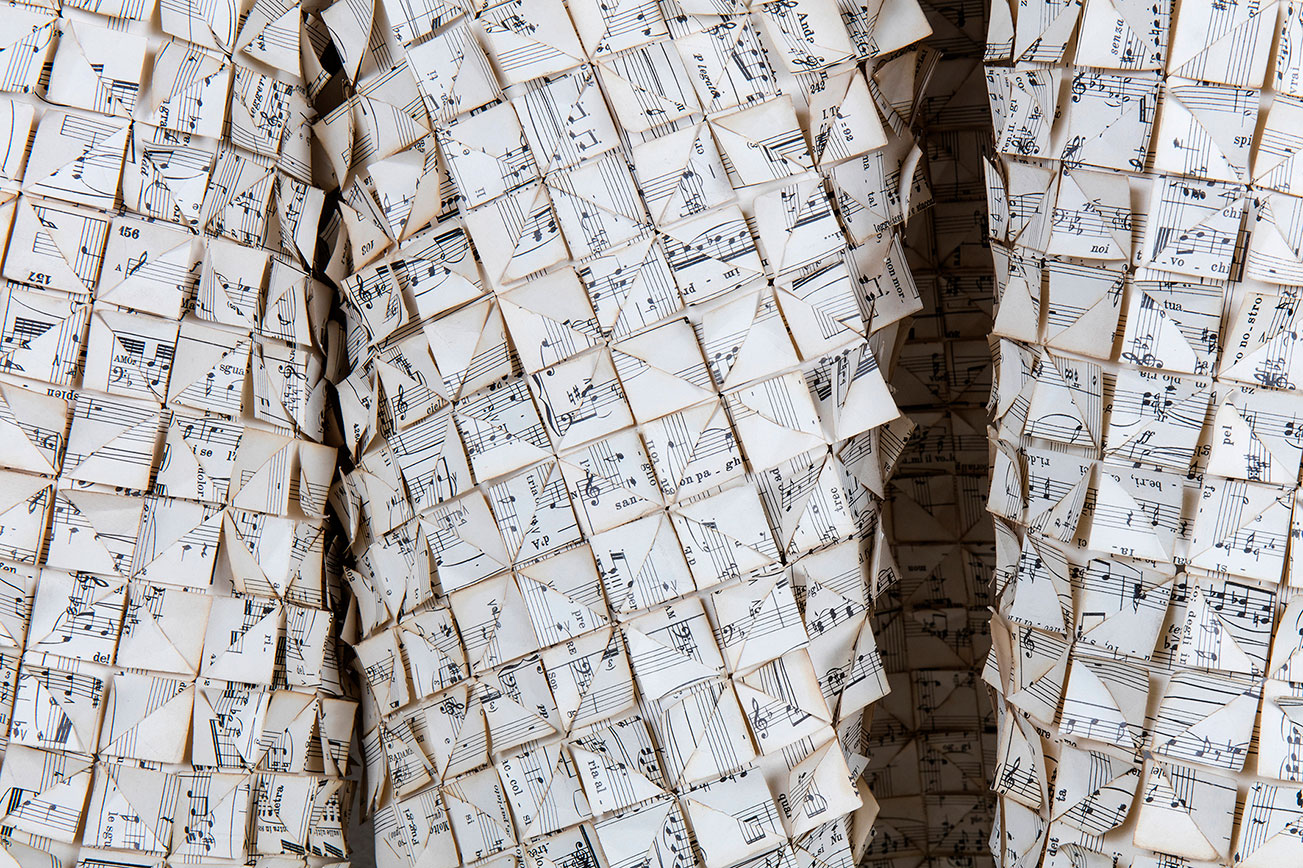

In the work The Sorrows of Absence, 2018 Swinburn uses pages from an archaeological book that has reproductions of historic sites that have been recently destroyed. Through presentation and representation of these images, the artist explores the concerns and effects of the loss of National Identity in these states. Swinburn reconstructs by folding the pages into each other in an attempt to repair what was destroyed. In this way, the sculpture creates a monument that revolutionises its previous history and references the change in their time and place. Swinburn captures the ephemeral conditions of performance with photography and disseminates these images either on marble or stone. In a way, the monumental nature of the work returns and is reformed from the fragile materiality of paper to a symbolic material such as marble or stone to signify its cultural significance.

The process in which Catalina Swinburn creates her interpersonal work emphasises on the human necessity of the conditions of being, loss and destruction. Regenerating these narratives articulates a sense of urgency and a mode of resistance. With the continuous struggles globally and displacement of human beings, Swinburn expresses hope and freedom to the world and anticipates an openness for cultural dialogue.

RITUALS OF IDENTITY

Justo Pastor Mellado

An entire complex work is not usually analysed on the basis of the singularity of a piece whose image is reproduced in a catalogue. Neither is it common to force the nature of a catalogue in order to recognize in it an editorial expansion of the exhibition space. However, we must be prepared to have a minimum understanding, namely, the ruin of the book as a dismantled monument that preserves the existence of the house of letters.

I suggest that readers consider this catalogue as an “instructions manual” to access Catalina Swinburn’s work. The texts do not necessarily add legibility, but provide us with a cultural distance that can only be understood if we pay attention to certain considerations; in other words, the “ways of doing” in the first place and secondly, the graphic effects on the territory.

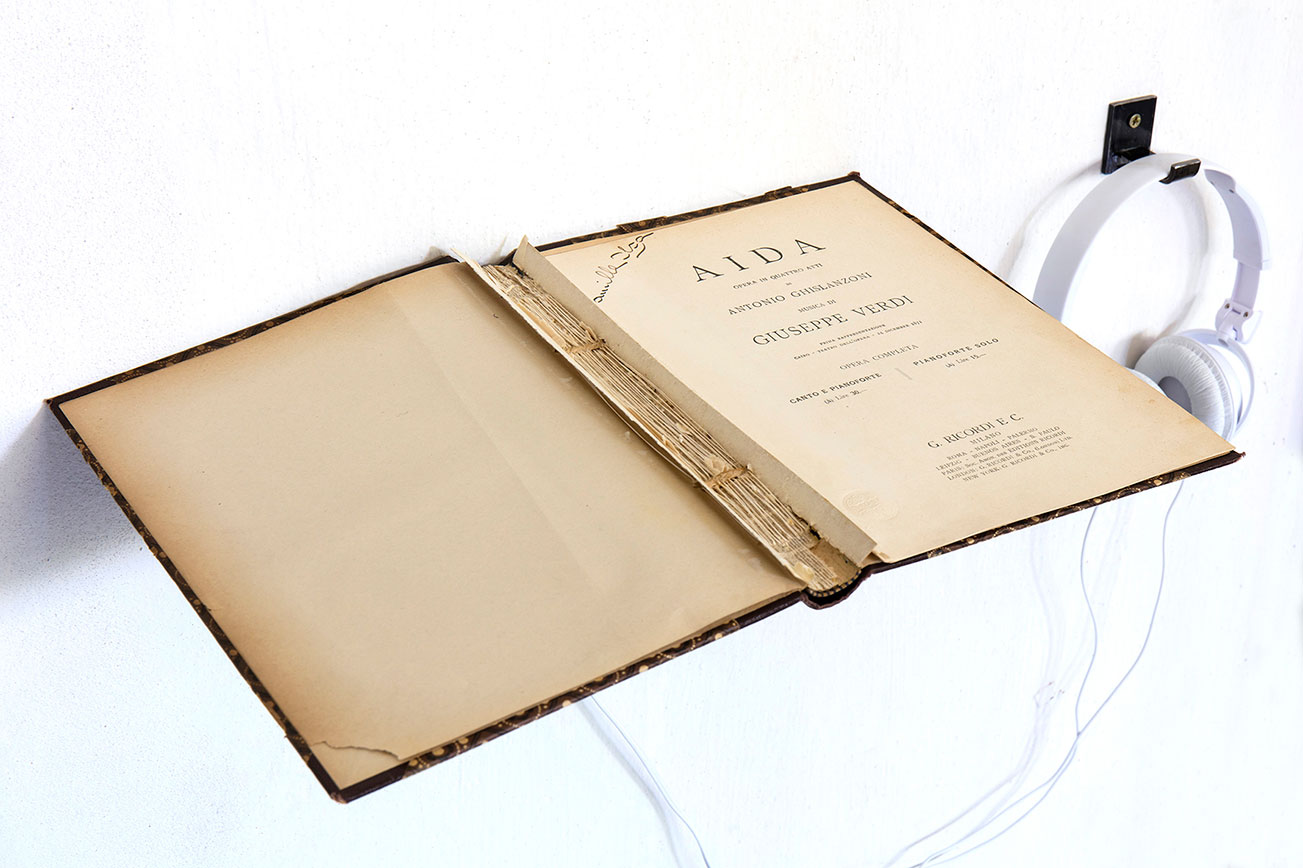

With regard to the former, the catalogue reproduces the image of a book in a state of de/composition revealed by the ostensible number of pages that has been ripped off. By tearing the binding of a book, its damaged spine is exposed, with its pieces of paper and the visible threads. It is one of many images and yet, it establishes the legibility of the set of pieces reproduced. In this regard, it underscores a cultural catastrophe, for the destruction of a book is comparable to the demolition of a building, even more so when we learn that the book includes the score of Verdi’s opera “Aida”, which conveys an idea of sentimentality that can be seen in the underlying configurations of power.

The pages – ripped, folded and transformed into coded messages already destined to such a purpose by the folding – mark the line that determines the scope of an enigma.

The origami thus restructures the ruins of the book to prepare them for an unimaginable role, as the singular components of a new object: a blanket, a dress. In the catalogue, the book appears as remains, since it shows the destruction of the binding to give way to the making of a blanket that can be used as a garment or a shroud.

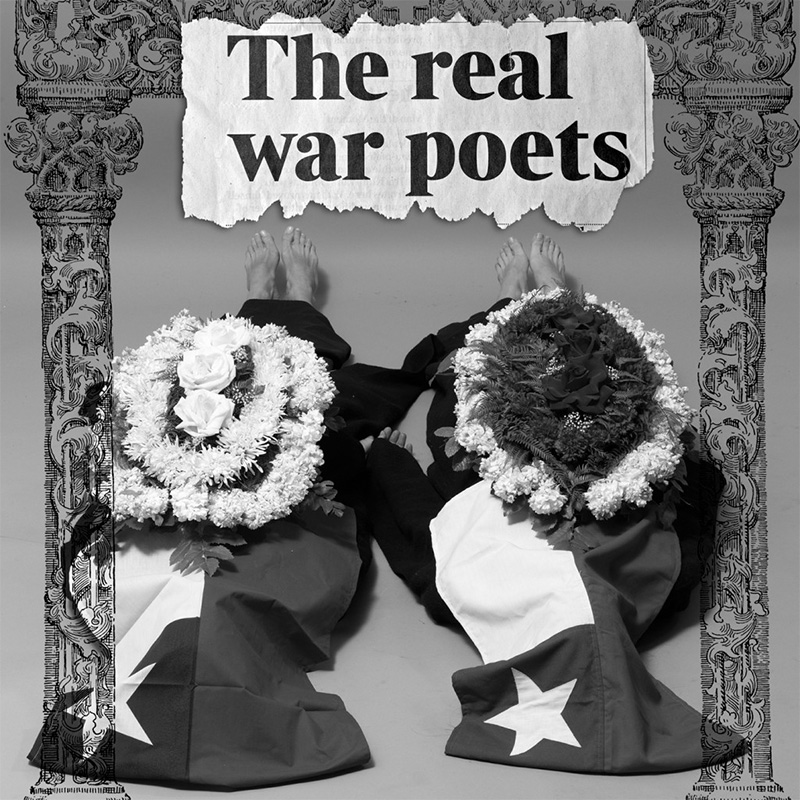

The above leads to the second consideration introduced in the first paragraphs: the graphic effects on the territory. It is clear that the first consideration yields two anticipatory effects: the visible injury (the destruction of the binding) and the folding (marking out and setting the boundaries of the surface). Here the design of the catalogue symbolizes grief with drawings on the sand, cracks on walls, and fences on borders and cemeteries.

We must talk about these photographs: a plan of the house is drawn on the sand, creating a meeting point somewhere between the anecdotal and the encyclopedic memory, under the threat of being completely swept away (covered) by the waves. The plan is drawn straightaway to show how the return of the repressed works.

In contrast, the photographs of the cracks ostensibly call for realism through controlled re appropriations of traumatic experiences, which are in turn reabsorbed by the art space.

This inevitably reminds me of the 1985 earthquake, which damaged the Fine Arts Museum of Santiago de Chile. Although there were cracks on the walls, the museum never closed, because the specialists in the resilience of materials had concluded that the building had no structural damage. However, the restoration work took so long that the cracks became “part of the building”.

As I accompanied a European curator on a tour of the museum, he asked about the author of this work, which boldly challenged the museum institution by exhibiting its cracks. I hated myself for correcting his error of appreciation. As we never had Greco-Roman ruins, we had to invent, to our convenience, symbolic destruction through commemorative constructions in territories of major migratory conflicts that survive as enclaves of the worst nineteenth century colonialism. This is when the photographs of Egyptian excavations are comparable to those of Darwin cemetery on the Malvinas Islands, which close the Rituals of Identity series. We look at some ruins from the point of view of other ruins, including the ruin of narratives and bodies.

“Aida”, whose pages are ripped off to make portable sarcophagi of the letter, makes the tombstones of the unidentified fallen become archaeological findings of a present that is forcefully acknowledged as the vestige of a damaged memory.

Justo Pastor Mellado

Art critic and independent curator.

Director Center for Art Studies (CEdA)

www.justopastormellado.cl